Would You Say Things have Improved With the Way Women Give Birth in the Last Century or so?

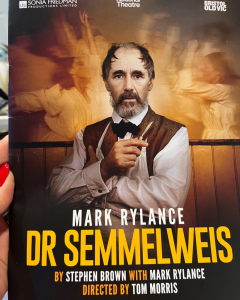

Recently I went to see a production of a play called Dr Semmelweis starring Mark Rylance (he of The BFG and Ready Player One fame.) Regular followers will know I am a huge fan of the theatre but my interest in this particular show was not just because it was an opportunity to see one of my favourite actors tread the boards but because of the subject matter.

Dr Ignaz Semmelweis was the man who discovered that if Dr’s washed their hands between performing autopsies and sticking their hands up inside the birth canals of labouring women, the maternal and infant death rate would drop by up to 90%.

In This Day and Age that sounds Obvious, Right?

Spoiler alert, no one believed him, and he ended up dying in a lunatic asylum.

I’d like to be able to tell you that this is a complete work of fiction.

I’d like to be able to tell you that things have improved significantly.

Unfortunately, I can’t!

The play was beautifully performed and the majority of the time Semmelweis was on the stage he was accompanied by ethereal ballet dancers representing the ghostly forms of the thousands of mothers who had died by his and all the other Dr’s hands. A fact that haunted him into madness – well that and the fact he couldn’t get anyone to believe what he was saying.

Dr Ignaz Semmelweis

was a Hungarian Dr working as an assistant to Professor Johann Klein in the First Obstetrical Clinic of Vienna General Hospital (he was sort of a Chief Resident for those who speak ‘Grey’s Anatomy’) His duties were to examine patients each morning in preparation for the professor’s rounds, supervise difficult births and teach students of obstetrics. These maternity institutions were set up all over Europe to address the problems of infanticide of illegitimate children. They were set up as free institutions and offered to care for the babies, which appealed to many underprivileged women including the poor and prostitutes as they were not often in a position where they could look after their own children. In return for the free care, the women were expected to have doctors and midwives in training working with them.

Childbed Fever

At the Viennese hospital, there were two maternity clinics; the First Clinic (the one the Dr’s worked in) had an average maternal mortality rate of about 10% due to ‘Childbed Fever’ (what we now know of as puerperal sepsis). The Second Clinic (ran by midwives) had a maternal mortality rate that was considerably lower, averaging less than 4%. This was a known fact to both those inside and outside the hospital, so much so that the women would beg to be admitted to the Second Clinic but as the clinics admitted on alternate days it came down to luck of the draw as to when they went into labour and therefore where they ended up. Because of this many women chose to give birth on the streets, pretending to have given birth suddenly on the way to the hospital (known as ‘street births’) which meant they would still receive the childcare benefits even though they had not been admitted to the clinic.

Dr Semmelweis was amongst the only people who found this puzzling.

Most other people were happy to blame childbed fever on the ‘immorality’ of the unwed mothers, or their corsets being laced too tightly or breast milk backing up into their systems or the general insufficiency of a woman’s body (I really wish I was making this up.) As far as he could see, the only differences between the two clinics after excluding everything else was that the First Clinic was where the medical students (men) did their training whilst the Second Clinic has been selected for the instruction of midwives (women) only.

Semmelweis realised, through a series of events, that this was extremely significant because only the male doctors were allowed into the ‘Dead Room’ to witness and perform autopsies as part of their training (women were considered far too delicate and fragile to be able to witness such things and they wouldn’t be able to understand it anyway – again, I wish I was making this up.) These same doctors were then transferring tissue from the dead and infected bodies into the birth canals of the women – thus resulting in puerperal sepsis.

Seems straight forward, right? Wash your hands! Don’t spread disease. Yes?

No! Semmelweis’s hypothesis that all that mattered was cleanliness was largely rejected and ignored. Partly because he couldn’t give a scientific explanation, he just knew that washing the hands worked. And partly because he was Hungarian, a much smaller country than Austria, therefore the Viennese Dr’s took offense at him telling them what to do. And after all, it was only the women that were dying so nothing really to get so worked up about!

He was dismissed from the hospital for political reasons and eventually moved back to Budapest after being harassed by the medical community in Vienna. He was outraged by the indifference of the medical profession and began writing increasingly angry letters to renowned European obstetricians often denouncing them as irresponsible murderers. Nearly 20 years after his discovery he was committed to a lunatic asylum where he died of septic shock after being severely beaten by the guards.

The story is tragic and haunting and there were so many moments during the performance that you could have heard a pin drop but I wonder how many people in the audience had the same realisation that I did. All these years later and nothing has changed.

Yes, thankfully, Dr’s know about hygiene and the importance of hand washing

but anyone (doula’s, midwives, antenatal teachers, the hypnobirthing community) who suggest alternative ways of viewing birth (i.e. as a medical condition) are dismissed by the Dr’s, the media and the public.

Parents-to-be have very little say about what happens to their own bodies being, on many occasions, forced to acquiesce to the ‘superior’ knowledge of those with a medical degree. They are made to feel, at best, insignificant and at worst, stupid, if they dare to broach the subject of not having internal examinations and submitted to someone else’s hands inside their vaginas several times throughout the labour.

The maternal morbidity rate in technologically advanced countries has risen and Black and Brown mothers are 5 times more likely to die during childbirth than their white counterparts due to institutional racism.

Iatrogenic harm (harm caused by medical treatment) is very real and yet women are either expected to put up with it because giving birth is expected to be traumatic and dangerous or they choose to have the modern-day equivalent of ‘street births’ and opt for a ‘free birth’ which is outside the maternity system.

Dr Elinor Cleghorn author of ‘Unwell Women – a Journey through medicine and myth in a man-made world’ writes in the programme:

“Imagine how many lives would have been saved, in childbirth and beyond, if male physicians throughout history had afforded women a voice.

Thanks to advances in medical knowledge, and pioneering figures like Semmelweis, maternal mortality from postpartum infection has reduced significantly. Yet women across the globe continue to lose their lives during and following childbirth to preventable causes and complications. History shows us that so much unnecessary suffering and death can be mitigated by listening to women, trusting their knowledge about their bodies, and respecting their wishes and needs. When we deny women their agency and autonomy, we are haunted by those thousands of women pushed to the margins of medicine’s history.”

In no way do I think what I do, is going to change the world, but it will change one birth at a time. If you want to join me and make a difference to your client’s birth experiences, get in touch to see how I can help you do that.